Recently I received a message from a friend at Switzers Vintage in Chilliwack British Columbia. He showed me a photo of an old roll of 120 film that had come into his possession. Knowing that I develop a lot of vintage film, he asked if I wanted to try and develop it. Of course, I said yes.

Several days later, I made the trip to Chilliwack to retrieve the film. Looking at the roll in my hands, my heart sank. It appeared the Kodak Panatomic film hadn’t been exposed. If it had been rolled through a camera, I’d be seeing the opposite end of the backing paper with the word Exposed. Instead, I was looking at the start of the roll, suggesting it hadn’t made a trip through a camera.

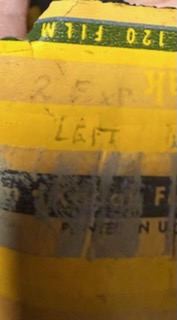

Back in my studio, I examined it more closely and noticed faint writing on the paper: 2 Exp Left. Could it be that the film was partially shot and then re-rolled onto the original spool to save the remaining frames for later? Not a simple process with many cameras, but fairly common among pros and serious photographers of the era. It was worth a try.

I then set about estimating the film’s age, which would help determine optimal development times. Panatomic was introduced around 1933 and remained popular into the early ’90s. This roll had a metal spool, not plastic, and the distinctive yellow-orange backing paper with simple text and no graphics. Most likely, it was manufactured in the mid-1950s, making it somewhere between 65 and 75 years old.

Next, I had to choose a development method. I immediately ruled out stand development, which tends to produce faint images on vintage film. These latent photos had been sitting for nearly 70 years, and they’d need a little extra kick. My developer of choice for very old film is Rodinal. It might introduce some fogging, but it excels at pulling out detail, which is more important. I used a longer fix time and a slightly cooler development temperature to help minimize fog.

I mixed the chemicals and set the timers. Eventually, the film sat in the final rinse stage, and I prepared myself for disappointment: a blank, unexposed roll. The darkroom timer buzzed. I pulled the film out… and there were images. Only three, but they were there. I hung the film to dry.

The last frame was a double exposure, but the first two were clear. One was a portrait of a young woman in front of a Christmas tree. The third image, however, was particularly intriguing.

It appeared to be a public event. A man in a dark hat stood on the right, holding what looked like an 8mm movie camera, possibly a reporter? A couple of other photographers were visible in the crowd. The attire matched Vancouver in the 1950s, which aligned with where the film was found. But where was this scene, and what was happening?

I shared the image on social media and received a flood of responses. Many identified the location as the Vancouver English Bay Bathhouse. Comparing archival photos confirmed the match. But what was the event?

Some suggested the annual English Bay Polar Bear Swim, held every New Year’s Day since the 1920s. But the mood was off. There were no smiles, no shivering swimmers wrapped in towels. The crowd looked solemn.

Then came a breakthrough. A few followers proposed it might be the demolition of the English Bay Pier, which was dismantled in 1958 due to decay and redevelopment plans. In January of that year, crowds gathered to witness its final moments.

Photo Source – Vancouver Archives CVA 677-95

I suspect that’s what we’re seeing. While the crowd watched the pier come down, the photographer turned their lens toward the onlookers, capturing not the spectacle, but the people witnessing it. A quiet inversion. A frozen moment of collective memory.

A few days later, I received a message from a follower. His father, now 91, had worked for Vancouver’s Public Works Department for over 40 years. He showed him the photo. Without hesitation, he said:

“Oh yes, I remember it. That was the day the pier came down.”