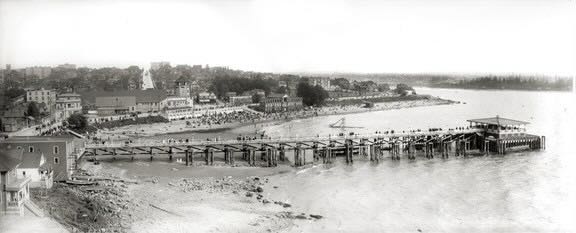

Some repairs feel purely mechanical. Others feel like opening a small door into the past. Replacing the ground glass on a Baby Graflex press camera — a compact little workhorse from the 1930s — sits squarely in the second category. These cameras were built for speed and clarity in an era when photography was still equal parts craft and improvisation, and their focusing screens were the quiet heart of that workflow. When the glass breaks, the camera doesn’t just stop functioning; it loses its voice.

In this story, I walk through the process of fitting a new ground glass into a camera that has already lived several lifetimes. It’s a simple repair on paper, but one that rewards patience, precision, and a bit of reverence for the people who once relied on this machine.

The focus screen on these old cameras is a special piece of ground glass that sits the same distance from the lens as the film. The photographer can use the ground glass to focus the camera and when it’s ready the film sheet is slid into position to capture the image.

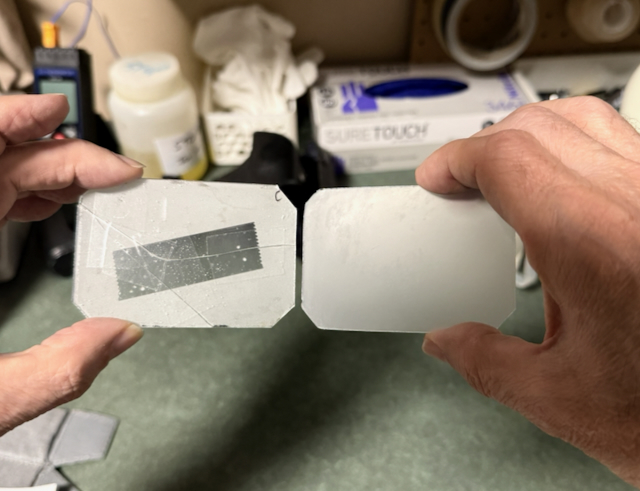

In this camera, somewhere over the past 90 or so years, the ground glass became damaged.

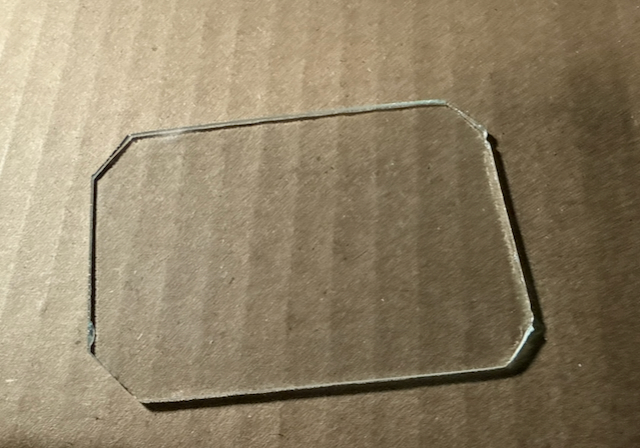

Today we will fix that! We start by cutting a new piece of glass to size and shape.

Of course, a plain piece of glass won’t work — light would simply pass straight through. The side facing the lens needs to be etched so it can act as a surface for the image to form. I start with an extremely fine diamond grit.

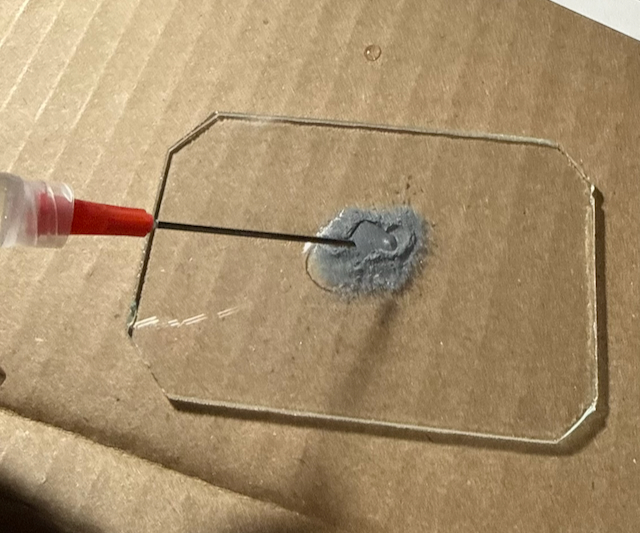

A bit of water turns the grit into a slurry.

The slurry is then sandwiched between the new glass and another plate of glass attached to a handle. With steady pressure and a circular motion, the grit slowly grinds the surface. Over time, the new glass takes on an even, matte texture.

The grinding continues until the surface is perfectly even and the new glass takes on a translucency that matches the original.

Now lets try it out

Yes — the image is supposed to be inverted. This is how photographers see the world on these vintage cameras: upside down and reversed. What matters is that the new glass is bright, and the focus snaps in cleanly.

With that, the 1939 Baby Graflex can go back to doing what it was made to do: making beautifully sharp images.

And if you’re wondering about the name, “Baby Graflex” refers to the film size — 5×7 cm — compared to its big brother, the Graflex Speed Graphic, which shoots 10×12 cm film.

If you’ve ever wondered what it takes to keep these old cameras working, or you just enjoy seeing the inner life of a tool restored to purpose, this is a satisfying little journey.